Meteor scatter communications is a rare and fascinating mode of ham radio. It uses radio signals that reflect off tiny rocks that enter the atmosphere at high speeds during meteor showers. These showers happen several times a year with the largest in August and December. To use this mode, you need to prepare well, have special software, and ideally a lot of power, which is fortunately available at the Clubhouse. We decided to try this mode during the Perseids meteor shower on August 12th.

We used the Flex 3000 transceiver and the Elecraft amplifier in the HF room, both of which can operate on 6 meters which is the predominant band for meteor scatter communications. The Elecraft can run more than 1000 watts on 6 meters, which is around the power level that we used. We needed a long coax cable to connect the amplifier to the six meter beam connector in the VHF room. Luckily, Todd KD2ESH had brought a 50 foot cable with connectors, and we joined it with another 50 foot cable to reach from the amp to the antenna connector. We set up the WSJT program on the Flex radio and chose the MSK144 protocol for meteor scatter. We pointed the beam to the west since that’s the direction in which most stations are located; however, this might not be the best strategy because we should aim at the meteors and not the stations. Unfortunately we didn’t know the best direction to aim at the meteors at that point.

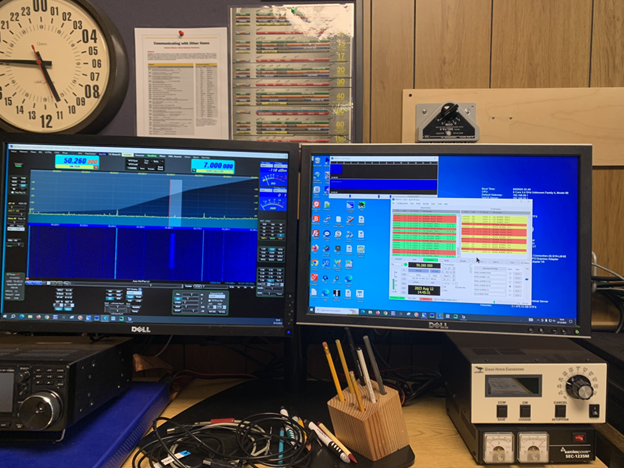

Figure 1- The Flex SDR program and WSJT receiving meteor signals

Most articles about meteor showers focus on seeing meteors which only happens at night, but radio operation can obviously happen anytime. When we started on Saturday morning we found many stations on 50.260 MHz, the standard frequency for meteor scatter. MSK 144 works like other digital modes: it transmits for one time slot and listens for another time slot and repeats this cycle. We had to choose whether to transmit on even or odd time slots and followed an article that suggested using even time slots for stations beaming to the west. MSK 144 is similar to other digital modes in that you only need to start the contact and the software will do the rest. But because meteor scatter is unpredictable, contacts can take a long time because you need a meteor to fly by while you’re transmitting and receiving. Some contacts took several minutes to complete.

We also had to separate contacts that came from meteors from those that came from direct or ionospheric signals. The waterfall display on the Flex radio was very helpful for this. A real meteor signal looks like a short burst that is easy to see and differentiate from a long signal from a local station. The grid square of the station also helps to tell apart meteor contacts from local contacts. Saturday morning was the best time for us, and we worked stations in Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Kentucky, and Orlando. Todd KD2ESH, Ralph KE2AHX, Al KB2AYU, John W2HUV and Mario W3CGS showed up that morning and were able to watch some of the contacts being made.

.

Figure 2 – KB2AYU and W2HUV working meteor scatter

We used the PSK reporter program to check if other stations could hear us. The screenshot below shows the stations that heard us on Saturday morning. Some of them were very far, like Dallas, Nova Scotia, and Orlando. The local stations probably heard us directly, but the distant ones probably heard us through meteors.

Figure 3- PSK Reporter showing stations hearing W2MMD

We wanted to do our main operations on Saturday night, when the meteor shower was at its peak, and about 10 members came to join us, but unfortunately the conditions were not good for viewing or radio contacts and we only made one contact that was likely from a meteor. We also had some very strong local stations and realized that we had to use the same time slot as them or they would block the weaker signals. This meant that two local stations on different time slots could ruin our chances, but luckily that did not happen. A larger group showed up that evening including Mike N2WOQ, Mario W3CGS, Marc WM2Y, Court KD2SPJ, John K2ZA, Mickey W2EFR, Lee N2LAM and Al KB2AYU along with several XYLs and SOs.

One of the challenges was not knowing where the meteors were coming from so we did not know where to point the beam antenna. On Sunday morning, we found a link to the “Virgo” program shown below which appears to show the direction to aim the antenna at any time. At that point it was too late for us to use it but we will try to learn more about it and use it next time.

Now that we’ve figured out how to successfully make meteor contracts we’re going to try some upcoming events. The next two major showers are the Leonid that peaks on November 17 and the Quadrantids that peaks on January 3, 2024. In the meantime, we’ll try to build some more knowledge of effective meteor scatter operations, and all members are invited to join in and participate. Links to some useful resources are below.

http://www.arrl.org/files/file/QST%20Binaries/nt0z.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meteor_burst_communications