This article accompanies the Tech Saturday presentation on SDR use in January 2025. Materials from that seminar will be available nearby after it’s presented.

1. Introduction & Why SDR Matters to Hams

Software Defined Radio isn’t just the latest buzzword—it’s the biggest change in amateur radio since the transition from tubes to transistors. In the past 15 years, SDRs have given us panadapters on radios that never had them, turned $30 TV dongles into all-band receivers, made weak-signal digital modes practical for the average ham, and allowed entire stations to be operated remotely over the Internet.

In this presentation and article we will focus on the type of SDR that most hams think of when they say “SDR”: separate, compact hardware devices that connect to one or more antennas at one end and to a computer through a USB port (or occasionally Ethernet) at the other end. These devices send raw I/Q data to the computer, where free or low-cost software does all the tuning, filtering, demodulation, and even transmission. Many modern ham radios (FlexRadio, Apache Labs ANAN, SunSDR, Icom IC-7300/7610, etc.) use SDR techniques internally, but they are complete, self-contained transceivers with built-in displays, controls, and often power amplifiers. They are outside the scope of this discussion—we’ll be concentrating on the inexpensive, open, USB-connected SDRs that have revolutionized the hobby for the average ham.

2. What “Software Defined Radio” Actually Means

At its core, an SDR “radio” is a small hardware device that connects to one or more antennas at one end and to a computer (or sometimes a tablet or smartphone) through a USB port (or occasionally Ethernet) at the other end. The device itself contains the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) and any necessary front-end circuitry, but it does very little processing on its own. Instead, it simply digitizes the incoming RF signals and sends the raw data stream to the computer, where the real radio work—filtering, demodulation, tuning, and even transmission for TX-capable devices—happens in software.

The key revolutionary feature of SDRs is the separation of hardware and software. Unlike a conventional radio where the manufacturer decides forever how the radio will behave, SDR hardware and SDR software are largely independent and interchangeable. Most modern SDR programs (SDR#, SDR Console, SDRAngel, GQRX, etc.) support dozens of different devices through open-source libraries such as SoapySDR or libiio. This means you can buy an RTL-SDR today, an SDRplay tomorrow, and a PlutoSDR next year—and keep using the exact same software you already know. The few exceptions are proprietary ecosystems, but the overwhelming trend is toward open, interchangeable platforms.

Best of all, nearly all of the popular SDR software is either completely free (SDR#, GQRX, CubicSDR, SDRAngel, etc.) or available at very low cost (SDR Console has a modest registration fee for the full version). This makes it possible to start with a $30 RTL-SDR dongle and a free program and still have a powerful, flexible radio station.

3. The Magic of I/Q Signals

Think of a regular AM or FM radio: it only needs to know how strong the signal is at any moment, so it throws away half the information the instant it demodulates. An SDR is much smarter—it keeps everything.

The hardware looks at the incoming radio wave from two directions at once, 90 degrees apart—like having two tiny antennas inside the box, one pointed east-west and one north-south. The “I” (In-phase) channel records what the east-west antenna sees, and the “Q” (Quadrature) channel records the north-south view at the exact same instant. By keeping both measurements, the computer has the complete picture: not just how loud every signal is, but exactly where it is in its cycle at every moment.

What actually travels from the SDR to the computer (via USB, Ethernet, or network stream) is a continuous river of paired numbers: I-value, Q-value, I-value, Q-value… This is the raw I/Q stream—the entire chunk of radio spectrum, perfectly preserved in digital form.

How much spectrum you can see at once is set by the device’s maximum sample rate, which determines the instantaneous bandwidth. A typical $30 RTL-SDR gives you about 2–3 MHz of visible spectrum at once—plenty for one ham band or a satellite pass. Mid-range receivers like the SDRplay RSPdx or Airspy Mini can deliver 8–10 MHz in a single window, letting you watch the entire 6-meter band or multiple satellite transponders simultaneously. High-end devices such as the Ettus B210, LimeSDR, or certain FlexRadio models can push 30–56 MHz or more of instantaneous bandwidth—essentially an entire HF spectrum scope in real time.

Wider bandwidth comes at a cost: every megahertz of bandwidth roughly doubles both the computing power needed on your PC and the data rate that has to move from the device to the software. A 2.4 MHz RTL-SDR stream is about 12 MB/s (easy on a ten-year-old laptop and a USB 2.0 port), while a full 10 MHz slice can exceed 50 MB/s and will saturate a USB 2.0 connection or a weak Wi-Fi link.

Because the software receives the full, untouched I/Q stream instead of demodulated audio, you can tune anywhere inside that captured bandwidth, change filters, remove interference, or switch sidebands. The computer does all of the work that discrete components would do in traditional radio – just with more precision and better control. Filters can be created in an SDR radio that are much sharper than those from discrete components, and you can have as many of then as you want.

And because it’s just a data file, you can record the raw I/Q stream and play it back exactly as if the antenna were still connected. This is pure gold for satellite and weak-signal work. Missed the callsign on a fast LEO pass? Open the recorded I/Q file, retune, slow it down, and read it perfectly. Learning to decode a new satellite’s telemetry? Record one good pass, then replay that same I/Q file hundreds of times while you experiment—no need to wait weeks for the next overpass. A simple audio recording can never give you these abilities because the tuning and filtering information was discarded the moment the audio was created. With a raw I/Q recording, the second (or hundredth) time through is always better than the first.

All modern SDR programs make recording and playing back I/Q files a one-click operation—try it once on an FM satellite pass and you’ll never record just audio again.

4. Hardware Landscape – The Main Players (2025)

The SDR world spans four orders of magnitude in price and capability, and the differences come down to five key specs that matter to hams: instantaneous bandwidth, ADC resolution and dynamic range, frequency coverage and filtering, number of antenna inputs, and transmit capability.

Why Bandwidth Matters – And Why Most of the Time You Don’t Need Very Much For day-to-day ham operating, huge instantaneous bandwidth is nice to have but rarely essential. On 20 m phone an Extra-class operator has 375 kHz of spectrum (14.150–14.350 MHz). The entire 2 m band is only 4 MHz wide. In these situations 1–3 MHz of SDR bandwidth is more than enough. Wide bandwidth becomes genuinely useful only for watching a full 6 m sporadic-E opening, monitoring wide transponders on linear satellites, receiving DATV on 23 cm or 13 cm (2–8 MHz wide signals), or running microwave beacon surveys.

Why ADC bit depth actually matters An 8-bit ADC has only 256 steps—so a single strong signal eats most of them and everything else distorts. A 14-bit device has 16 384 steps and a 16-bit device 65 536 steps—meaning you can have a 100 kW broadcaster 50 kHz away and still copy an S2 DX signal cleanly.

Entry-level receivers (under $50) The RTL-SDR Blog v3 or v4 dongles (typically $25–$40) are still the most popular entry point into SDR for hams. These tiny USB devices cover roughly 500 kHz to 1.7 GHz (and HF down to about 100 kHz with the built-in direct-sampling mode on the v3/v4 models). They provide a usable instantaneous bandwidth of 2.4–3.2 MHz and use an 8-bit ADC. Because they lack any meaningful front-end filtering, strong nearby broadcast stations can overload them on lower bands, especially HF and low VHF. Despite that limitation, the RTL-SDR is generally adequate for many purposes: learning SDR concepts, monitoring VHF/UHF repeaters, receiving ADS-B, trunked radio, and acting as a low-cost panadapter on a traditional rig. Its 2.4–3.2 MHz bandwidth is sufficient for most everyday ham operating needs (one band at a time), and the extremely low price makes it the perfect first SDR. The RTL-SDR also pairs beautifully with inexpensive Raspberry Pi computers for dedicated, single-purpose receiving projects (see the new section below). For serious, regular ham operating—especially on crowded HF bands or when you need maximum dynamic range—the lack of internal filters and the 8-bit ADC make it less than ideal, but for learning and casual use it remains unbeatable value.

Mid-range dedicated receivers ($100–$350) The SDRplay RSP series (RSP1A, RSPdx, and RSPduo) delivers excellent performance at a very reasonable price. These receivers cover 1 kHz to 2 GHz with a 14-bit ADC and up to 10 MHz of instantaneous bandwidth. They include switchable front-end filters for different bands and selectable notch filters to remove strong FM broadcast stations, which dramatically improves HF performance compared with the RTL-SDR. The RSPduo adds a second independent receiver, making it ideal for diversity reception or monitoring two bands simultaneously.

The Airspy HF+ Discovery and Airspy Mini/R2 are specialized receivers that achieve extraordinary dynamic range on HF and low VHF. They use polyphase harmonic rejection mixers—clever analog circuitry that mathematically cancels out unwanted images and harmonics before the signal reaches the ADC. This means you can open the entire 0–30 MHz spectrum with almost no spurious signals from strong MW broadcast stations, even when using a simple long wire near a city. The HF+ Discovery is optimized for maximum sensitivity and blocking performance below 260 MHz, while the Mini/R2 offers 10–12 MHz bandwidth and the same clean front end for 6 m contesting, EME, or meteor scatter.

Affordable transmit-capable devices ($300–$500) The HackRF One (and its popular PortaPack add-on) is the classic “tinkerer’s SDR” for experimenters and satellite operators. It covers 1 MHz to 6 GHz in a single, half-duplex device, delivers up to ≈17 MHz of instantaneous bandwidth, and can transmit up to about 10 mW (more with an external amplifier). The 8-bit converters limit clean transmit power, but the wide frequency range and open-source firmware make it ideal for replaying signals (legal ones only!), testing ISM-band devices, experimenting with LoRa, decoding and transmitting satellite protocols, or building portable microwave links. The PortaPack version turns the HackRF into a self-contained handheld radio with a screen and controls, making it perfect for portable operations such as SOTA, field day, or satellite work.

The ADALM-Pluto (PlutoSDR) from Analog Devices started life as an educational tool but has become a favorite among hams for its full-duplex capability and low price. It covers 325 MHz to 3.8 GHz stock (easily modified to 70 MHz–6 GHz with community firmware), provides up to ≈17 MHz bandwidth, and uses 12-bit converters for much cleaner transmit signals than the HackRF. Pluto is widely used for digital voice repeaters, microwave experiments, building homebrew transceivers, and as a low-cost remote station head. Its full-duplex operation means it can transmit and receive simultaneously, which is extremely useful for satellite cross-band work, digital modes, or testing new modulation schemes.

5. Key Software Parameters You Must Understand

All SDR programs expose the same core controls, and mastering them turns any dongle into a precision instrument. The terminology varies from program to program: familiar ham-radio names appear in some (especially SDR Console), while others use more technical DSP terms. Here are the most common parameters and what they really mean to a ham operator:

Sample rate (or “Bandwidth” in some programs) – This is the total width of spectrum you can see at once. It is exactly the same as the “span” or “bandwidth” control on a traditional panadapter. A 2.4 MHz sample rate gives roughly 2 MHz of usable display—enough for one ham band or a satellite pass. Higher sample rates (8–10 MHz on mid-range receivers) let you watch several bands or an entire 6 m opening at once. Note that setting bandwidth larger than needed for your particular application will create unnecessary work for the SDR radio and your computer, and if you’re connected remotely to the SDR through Spyserver or some other program it will significantly increase the bandwidth on your network. Therefore it’s generally useful to decrease the bandwidth of your received signal through settings in the SDR software to the level needed for your particular task.

RF gain / IF gain / AGC – These are the same as the RF gain and AGC controls on any conventional radio. RF gain sets the front-end sensitivity; IF gain adjusts the level after the first conversion; AGC automatically reduces gain when strong signals are present. Most programs have a simple “AGC” button (fast, medium, slow) just like your rig.

FFT size & averaging – The FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) size controls how finely the spectrum is divided. Larger FFT = finer lines on the waterfall (better resolution) but slower screen updates. Averaging smooths out the noise so weak signals stand out—think of it as a digital version of the “slow” sweep on an old analog scope.

Decimation – This is a very useful but less familiar term. It lets the software throw away samples in a controlled way so you can display a narrow slice of spectrum (e.g., 50 kHz of 20 m CW) while the hardware is still running at full speed (10 MHz). This dramatically reduces CPU load and network bandwidth for remote operation, yet you still get the full dynamic range and filtering of the original wide capture. In SDR Console and SDRAngel it’s usually a drop-down or slider labeled “Decimation” or “Zoom factor.”

DC blocking / DC offset removal – Many SDRs have a small spike or “bump” right at the center frequency because of imperfections in the hardware. This control removes that spike so you can tune exactly to a signal without a big lump of noise in the middle of the waterfall.

Bias-T – Some receivers have a small +5 V supply on the antenna port to power active antennas, upconverters, or LNBs. This control turns that voltage on or off. It is the same as the “Bias T” switch on many ham rigs.

Offset tuning / Low-IF mode – This lets you move the displayed center frequency away from the hardware’s zero-IF point, avoiding the DC spike and any local-oscillator leakage. It is similar to using “split” or “offset” on a conventional radio to avoid a birdie.

Other common controls

Squelch – Exactly the same as on any FM rig.

Notch / Noise blanker – Digital versions of the same controls on your rig.

Audio gain – The volume control for the speaker or headphone output.

Get these settings right for your band conditions and your $30 dongle can outperform a $5,000 traditional radio on a quiet band.

6. Major Software Packages – Strengths & Sweet Spots

The SDR software world splits into two camps: programs designed primarily for operating (making and logging QSOs) and tools built for experimentation and signal analysis.

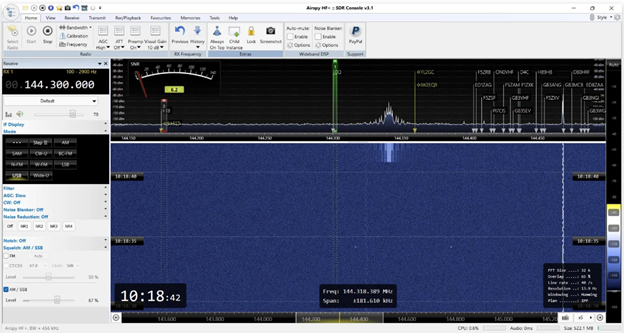

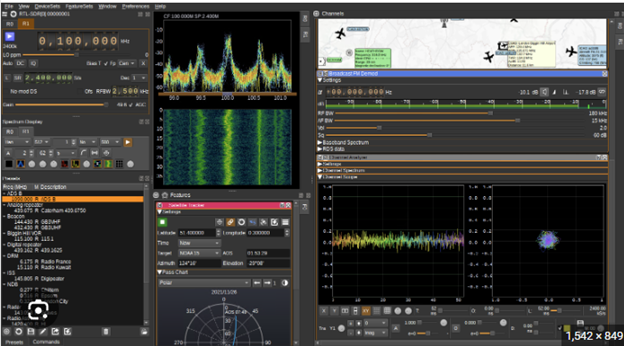

Operating-focused packages SDR Console v3 (by Simon Brown) is the professional-grade all-rounder most serious operators choose. It offers an outstanding spectrum display, built-in CW, SSB, and digital-mode decoders, full rig-control integration with Omni-Rig or Hamlib, logging, DX Cluster spots, and the best remote-server implementation available. Most club remote stations and big contest setups run SDR Console. It’s what’s used at the GCARC satellite station, too.

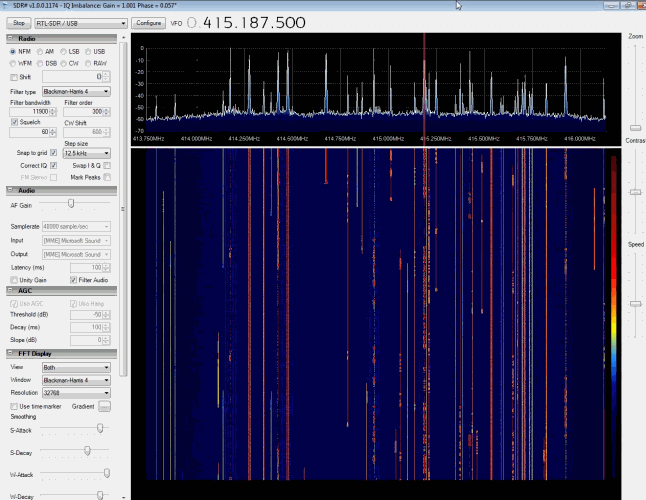

SDR# (SDR Sharp) remains the fastest, lightest, and most plugin-rich environment. It starts in under a second on any laptop and the Community Plugin pack adds frequency manager, DSD+ for digital voice, and dozens of other tools. It is perfect for casual ragchewing, quick demos, and everyday listening.

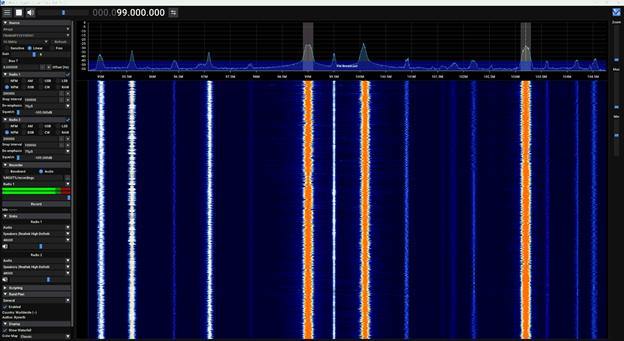

SDR++ is a modern, cross-platform alternative that feels like a polished version of SDR#. It offers excellent performance, low CPU usage, and a clean interface with good support for most hardware. Many hams use it as their daily driver for operating because it combines speed with a contemporary look.

SDR Connect is the official multi-platform client from SDRplay. It provides a straightforward, operator-friendly interface with excellent support for the entire RSP series and is especially popular for users who want a clean, no-frills program that just works.

Experimenter / signal-hunter package SDRAngel is the open-source powerhouse for anyone who wants to transmit or decode unusual signals. It supports transmit on Pluto, HackRF, LimeSDR, and other devices, allows multiple simultaneous receivers or transmitters on the same hardware, and includes built-in decoders for ADS-B, DAB, satellite telemetry, rotator control, and many other protocols. SDRAngel is the Swiss-army knife for satellite operators, microwave experimenters, and anyone who wants to go beyond standard voice or CW operation.

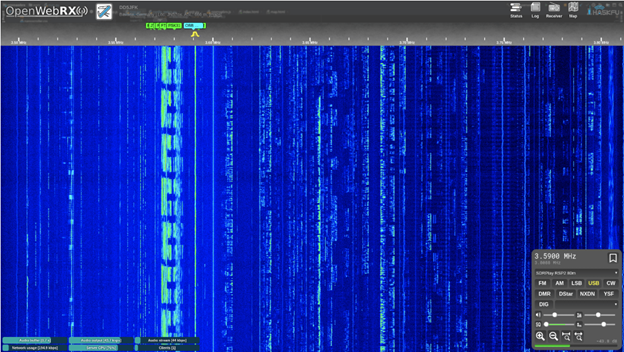

Open WebRX – browser-based public stations Open WebRX (and its fork OpenWebRX+) is a web-based SDR server that lets anyone access a remote SDR through a normal web browser with no additional software required. Hundreds of public Open WebRX stations worldwide are available 24/7, covering everything from HF to UHF. The big advantage is convenience—you can listen to a station on the other side of the world from your phone or tablet. The limitation is that you are restricted to the frequencies and modulation modes the station owner has configured, so it is not as flexible as running your own software on a local or remote SDR. It’s probably not a choice for an individual working with SDR radios but works well on a public resource, especially one for less sophisticated users. The GCARC has one of these set up at the Woodruff Middle School for use by their STEM students.

Most hams end up with one operating package they use 95 % of the time (usually SDR Console or SDR#) and one experimenter package (usually SDRAngel) for the occasions when they need to decode a new satellite, measure a filter curve, or transmit with a Pluto.

RTL-SDR + Raspberry Pi for dedicated, single-purpose receivers

The combination of an RTL-SDR dongle and a Raspberry Pi computer is incredibly popular for single-purpose receiving projects that run 24/7 without tying up a main PC. Because the RTL-SDR is so inexpensive and has enough bandwidth for most individual tasks, hams and hobbyists use this setup for many dedicated applications:

- Receiving GOES weather satellites (NOAA GOES-19) and decoding images with software such as goestools or WXtoImg

- Copying WSPR (Weak Signal Propagation Reporter) beacons on HF and VHF for propagation studies

- Monitoring APRS packets on 144.390 MHz (or 144.800 MHz in Europe) and feeding the data to aprs.fi

- Receiving and decoding 433 MHz ISM-band IoT signals (weather sensors, remote controls, tire-pressure monitors, etc.) with rtl_433

- Listening to aircraft ADS-B, marine AIS, or trunked radio systems

- Running a simple NOAA weather radio receiver or a dedicated FM broadcast monitor

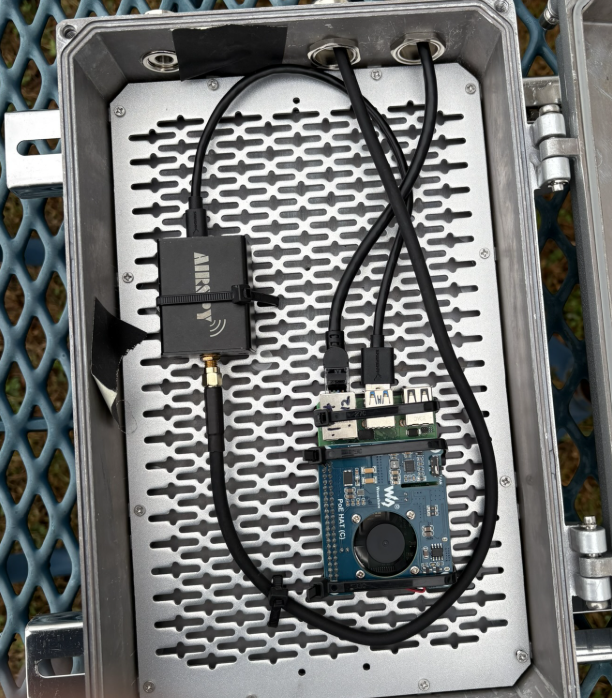

The Pi can run headless (no monitor or keyboard) and can be connected remotely through a command-line interface with a program like Putty or occasionally with a remote desktop-type program called VNC. You configure the software once, then let it run continuously. Power needs for these configurations are generally higher than for projects that only involve a Pi since it needs enough power to run the Pi, the SDR radio and any other devices powered by it, such as a preamp connected to the SDR and powered by a bias-T connection. Often a separate 3 amp supply is the minimum requirement for these projects, and 4 or 5 amp power supplies are not uncommon. Many people keep several Pi + RTL-SDR combinations in a rack or on a shelf, each dedicated to a different task. This is an inexpensive, low-power way to build a personal monitoring station without needing a full computer running all the time.

7. Remote SDR Operation – Bringing the Clubhouse to Your Shack

One of the most powerful features of SDR is that the radio no longer has to be in the same room—or even the same town—as the operator. SpyServer (from Airspy) is an excellent way to separate the SDR hardware from the operator when the antenna is distant from the operator but can still be connected through a local network, VPN, or public Internet.

At the Clubhouse we use SpyServer and an Airspy R2 mounted right at the Discovery dish antenna in a waterproof enclosure powered by Power-Over-Ethernet (POE) that lets a single cable from within the Clubhouse provide both power and network connection. This places the SDR close to the antenna (minimizing cable loss and noise pickup) while allowing members to connect to it from anywhere on the clubhouse network, through VPN from home, or even over the public Internet if we open the port. SpyServer is extremely lightweight and runs beautifully on a Raspberry Pi, a small PC, or the same computer that runs the SDR itself. It compresses the I/Q stream and sends it to any client running SDR# or SDR Console (or in the case of the Discovery dish the SatDump program for decoding satellite transmissions), giving you the full remote SDR experience with very low bandwidth usage.

8. Quick “Best Choice” Recommendations

- Simple panadapter or second receiver → RTL-SDR v4 or SDRplay RSP1A

- Serious HF DXing and contesting on a budget → SDRplay RSPdx or Airspy HF+ Discovery

- Portable go-kit with transmit (SOTA, satellites, emergency) → HackRF + PortaPack or PlutoSDR

- Weak-signal VHF/UHF (FT8, EME, meteor scatter) → Airspy Mini/R2 or RSPduo in diversity mode

- Full remote club station everyone can use → RSPdx, Pluto, or Hermes-Lite 2 + SDR Console server on a small PC or Pi

Start cheap, learn the concepts, then upgrade hardware while keeping the same familiar software. Welcome to the SDR revolution!